Last chance on the book: first pass pages

More than you ever wanted to know about this part of the process

Last week, we turned in another draft of MY SALTY MARY, which means it’s time for . . . DAWNBREAKER first pass pages,1 due this week!

In my Discord group, someone asked what pass pages entail. So I thought I’d talk briefly about how I used to do pass pages, how I do them now, and a couple of small difference between the two publishers I’ve worked with so far.

In case you don’t know what I’m talking about, this is the final stage (for authors) of a book’s production. This is when all the text gets laid out onto the page like a book, rather than a manuscript, so we’ll see the font they’re going to use, any design elements.2 If you’ve ever read an ARC,3 you’ve seen the bound version of first pass pages. They’re made from the same files.

First pass pages tend to have errors. Yep, even with all the careful line editing and copyediting multiple people have done on the manuscript so far, some errors still make it through. And sometimes, errors are introduced.

For example, when I was working on my very first first pass pages — INCARNATE — there was a section where the dialogue tags had been misplaced during the typesetting process (yes, I double-checked my manuscript and it was correct there!), so it made a conversation quite confusing. And a place where an entire paragraph was just “v.” I assume that was a copy/paste gone wrong.

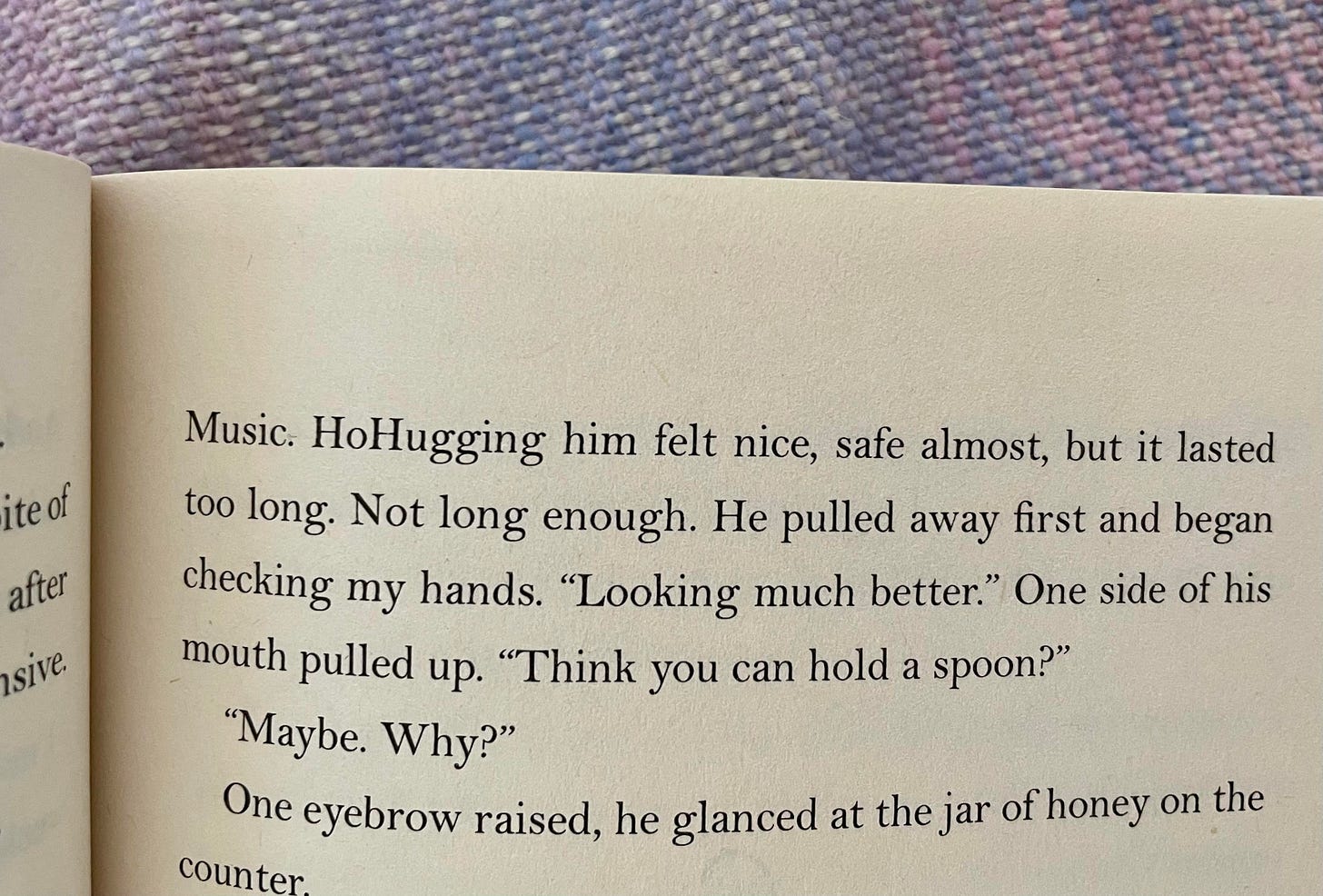

But most notably . . . HoHugging.

This is a photo of the ARC, since I don’t have the pass pages anymore, but remember, they’re the same file. So what I saw in my pass pages also printed into the review copies that everyone else saw.

What happened here? A sentence got cut off and the next line got added in.

This was my first ever pass pages. At first, I worried that ARC readers would think these were my errors and that I was just a lazy writer, but that didn’t happen. Everyone who got the ARCs understood what had happened. And very quickly, I learned to laugh at it.4

Basically, that is what we are doing at the pass pages stage: looking for any last-minute errors so that the book will be as clean as possible when it’s sent to the printer.

In the past, first pass pages came printed out on regular printer paper (I’ve also seen authors with extra large paper that fit two book pages, but mine were always regular copy paper). I’d get a massive box in the mail, instructions to make corrections onto the page using a green pencil, and send those pages (and only those pages) back to the publisher, where someone would manually add all my changes to the master file.

Eventually, though, many (most?) publishers moved toward digital pass pages, creating a PDF with annotations and corrections. Authors can make their own notes and just send the whole file back. Or, one thing I’ve done with the Janies, make a list of the requested changes (noting the page and line) in another document.

I don’t know about other authors, but I miss paper pass pages — mostly for the sake of my eyes, and because there was something nice about reading the whole book again on paper. Reading it as a PDF — even though it’s nicely laid out! — just isn’t the same.

I know, I could print it out, but I don’t miss wrangling a bunch of pieces of paper. After a few books, those can really pile up!5

Okay, so what does an author actually do with pass pages?

Well, we read them. This is the final time we’ll get to make changes to the book (generally), so it’s always a little tense — mixed with oh my gosh AGAIN?

The first thing publishers like to tell us is to not make very many changes. This is because the layout work has all been done. The paper allotted for the book has (probably?) been ordered. At this stage, too many changes can actually cost the company money — because of the time and labor to make substantial changes to the layout of the text, and the need to proofread again and again. In fact, according to author legend, too many major changes can actually cost the author money, though I’ve never actually seen this enforced, even when authors have talked about adding entire chapters to their books.

But basically, we are asked to not make any big changes to the book. The time for that has passed. This is for typos, clarity, last-minute grammar mistakes, and other small changes that will not affect the flow of the text down the page.

When I get my pass pages, I usually skim through to see what queries the proofreader left for me, just to get a sense of how much work that side is going to be. Then I figure out how much time I have to work on it. Often, it’s a few weeks. This time, it’s a little less than a week, just because of the way my deadlines overlapped. Which means I need to get moving. (To be honest, it doesn’t usually take me very long once I sit down to do it, because again, I’m not supposed to change much.) I set a page goal for myself — I will read through X pages every day to meet the deadline. (With this one, I’m aiming for 75 pages a day, but there’s a good chance I will be able to do more most days.)

And while I read, I make also make the changes into my Scrivener project for the book, because I am That Kind Of Author. (I do this in copyedits, too.)

One thing that’s been different for me with the Nightrender books — since I have a different publisher — is seeing extra notes from the proofreader. These aren’t for me, but for the in-house designer. (I assume these happen everywhere, just before the author sees the pages. There’s no right or wrong way, as far as I’m concerned. It’s just something I found interesting!)

These notes are largely about “bad breaks” — where a word gets broken into the next line, but it doesn’t always make for a smooth reading experience. Here’s an example from the opening:

The note says (basically) that it would be a much better reading experience if “reincarnated” were broken up after the prefix: re-incarnated, rather than rein-carnated.

That looks like an easy change to make, but keep in mind, since the text is justified to both sides (not ragged at the right side, like this post), removing even two letters from the first line is going to add a little more space up there . . . and adding two letters to the second line is going to remove space from between the words there.

My guess is that it will be just fine in this example; it will still look nice and be easy for the reader to read. But I’m sure you’ve read books where there was a line with such tight spacing between the words that it looked like a giant single word. Or where there was a ton space between the words. Sometimes there’s just not much you can do about it without changing the text a bit. (There’s at least one request for me in here, regarding spacing, to remove an ellipses, which would solve the problem.)

One thing that’s not pointed out in this book, but I know they’re looking for: rivers and lakes. You know when the spaces between words kind of . . . lines up and makes a little white stream down the page? Or when there’s a blob of white space? Those things catch the eye and make the reading experience a smidge less immersive, so someone has to fix them. But sometimes they’re unavoidable, or small enough it’s not a big deal to wrestle with.

At this point in production, it always strikes me how much care goes into making a book — not just on the writing side, but in the actual layout of the text. Someone is choosing the right font, noticing where words break unnaturally, and how the text looks on every single page. It’s invisible to most of us non-design people because it’s meant to be. Instead, it’s in service to making the book as immersive and clean as possible.

And even when I’m done with the first pass pages, someone will go through a second pass. And a third pass. Tiny fixes until they can’t find more errors and the book goes to print.

It’s such a careful, detail-focused process all the way through.

Okay, that’s pass pages! And if I don’t get back to mine, I’ll be in trouble.

The existence of first pass pages implies the existence of second and third and perhaps even fourth pass pages! And yes, there are more passes. But much of the time, authors don’t really look at these.

Sometimes those are still TK, though, especially maps and other elements that take a bit longer to create.

Advance Reader Copy — usually sent out to reviewers and booksellers to hype up a book within the industry!

Since this was my first experience, I assumed it was normal that pass pages had at least one very silly error. But nothing like this has ever happened again in the fourteen books I’ve read pass pages for since. I don’t know whether I’m relieved or disappointed.

I don’t have them anymore. I recycled them ages ago.

This is the most detail I’ve ever seen an author explain about pass pages. Thank you for making them less vague! Also, I’d never heard of the “rivers and lakes” concept but that totally makes sense.

HoHugging is a hilarious typo/error. I’m glad you can now laugh about it. 😂